Recently I found myself watching through some of the videos from the SciPy 2017 Conference, when I stumbled over the tutorial Numba - Tell Those C++ Bullies to Get Lost by Gil Forsyth and Lorena Barba. Although I have to say I find the title a bit pathetic, I really liked what (and how!) they taught. Because I found myself immediately playing around with the library and getting incredible performance out of Python code, I thought I’ll write some introductory article about the Numba library and maybe add a small series of more tutorial-like articles in the future.

So what is Numba?

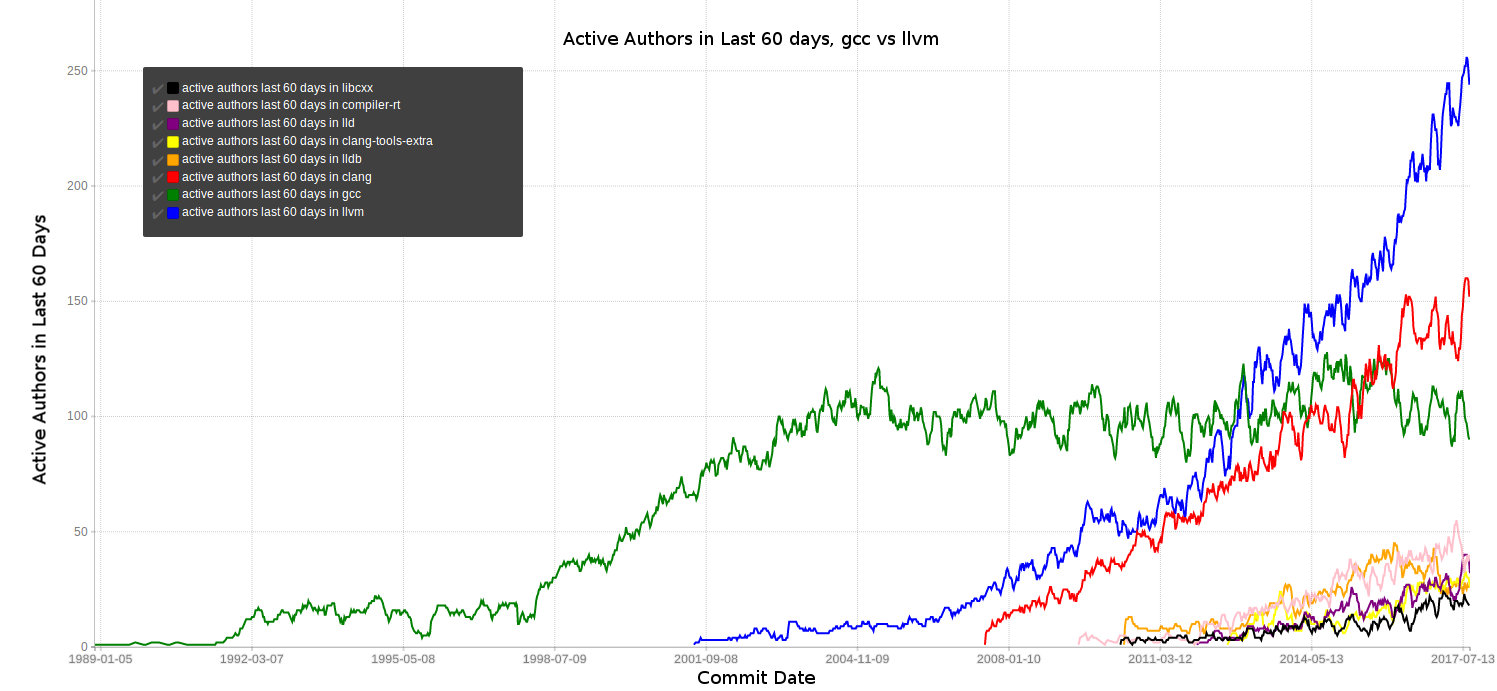

Numba is a library that compiles Python code at runtime to native machine instructions without forcing you to dramatically change your normal Python code (later more on this). The translation/magic is been done using the LLVM compiler, which is open sourced and has quite active dev community.

Active number of authors in the last 60 days. Graph by Nick Desaulniers from his blog. These might not be exact numbers, but show a good trend of the active dev community.

Numba was originally developed internally by Continuum Analytics, the same company who provides you with Anaconda, but is now open source. The core application area are math-heavy and array-oriented functions, which are in native Python pretty slow. Just imagine writing a model in Python, that has to loop over a very large array, element by element, to perform some calculations, which can’t be rewritten using vector operations. Pretty bad idea, huh? So “normally” these kind of functions are written in C/C++ or Fortran, compiled and afterwards used in Python as external library. With Numba, also these kind of functions can be written inside your normal Python module, and the speed difference is diminishing.

How do I get it?

The recommended way of installing Numba is using the conda package management

conda install numba

and this was for long the only way. But with the newest release, which is just a day old you should also be able to install Numba using pip. But as long as you are able to use conda, I’ll recommend using it, since it will be able to install e.g. the CUDA toolkit for you, in case you want to make you Python code GPU-ready (yes, this is also possible!).

How can I use it?

It doesn’t require much. Basically you write your “normal” Python function, and then add a decorator to the function definition (If you aren’t so familiar with decorators read this or that for an introduction). There exist different kind of decorators you can use, but the @jit might be the one of choice for the beginning. The other decorators can be used to e.g. create numpy universal functions @vectorize or write code that will be executed on a CUDA GPU @cuda. I won’t cover these decorators in this article, but maybe in another. For now, let’s just have a look on the basic steps.

The code example they provide is a summation function of a 2d-array (you probably would never calculate this way) but here is the code:

from numba import jit

from numpy import arange

# jit decorator tells Numba to compile this function.

# The argument types will be inferred by Numba when function is called.

@jit

def sum2d(arr):

M, N = arr.shape

result = 0.0

for i in range(M):

for j in range(N):

result += arr[i,j]

return result

a = arange(9).reshape(3,3)

print(sum2d(a))

As you can see, all that is done is, that a Numba decorator was added to the function definition, and voilá this function will run pretty fast. But here comes the caveat of the whole joy: You can only use Numpy and standard libraries inside the functions you want to speed up with Numba and not even all of their functionality. The good point: They have a pretty decent documentation, where everything that is supported is listed. See here for the supported Python features and here for the supported Numpy features (for the current version 0.35). But let me tell you, that’s enough! Remember, Numba isn’t meant to speed up your database queries or any image processing functionality of a third party library. Their aim is to speed up array-oriented computations and this can be perfectly done using their supported functions.

Example and Speed comparison

I’m not the biggest fan of this kind of examples like above, the typical Python user would never implement like this, but instead call numpy.sum. Instead I’ll give you another example, where you can’t simply fall back to a highly optimized library like Numpy. To better understand this example, maybe first a little background story (If you aren’t interested in the context of the code you’ll see in the example, you can directly skip this and go directly to the code).

From what I’ve studied, I would consider myself a Hydrologist and one thing we do a lot is to simulate rainfall-runoff processes. Simpler said: We have time series of e.g. rain and air temperature and try to model the how much discharge you can expect in a river to any given time step of that series. It might be a bit more complicated like this, but let me tell you: not much! So the models we typically use iterate over the input arrays and for each time step, we update some model internal states (e.g. storages that simulate the soil moisture, snow pack or the interception of water in e.g. the trees). At the end of each time step, the discharge is calculated, which is not only depended on the rain, that has fallen at the same time step, but also at the internal model states (or storages), which in their case are depended on the state and input of previous time steps. Well you maybe see the problem: We have to calculate the whole process time step by time step and Python is natively really slow for this! This is why most of the models are implemented in Fortran or C/C++, which only a few of us understand and the most just apply them. Python at the same time is used by more people, is far more understandable and easier to start with, but as said before: slow for this kind of array-oriented calculations. But what if Numba allows us to do the same thing in Python, without much of a performance loss? I think at least for model understanding and development, this might come handy (Therefore I created recently a project called RRMPG - Rainfall-Runoff-Modelling-Playground).

Okay now let’s check what we got. We’ll use one of the simplest models, the ABC-Model which was developed by M. B. Fiering in 1967 for educational purpose, and compare the speed of the of native Python code against Numba optimized code and a Fortran implementation. Please not that this model is not what we use in reality (as the name suggests) but I thought it might be a better Idea to give an example, which you have to implement from scratch and can’t fall back to e.g. Numpy.

The ABC-Models is a three parameter model (a, b, c, hence the name), that only receives rain as input and only has one storage. A fraction of the rain is immediately lost, due to evapotranspiration (parameter b), another fraction percolates through the soil to the groundwater storage (parameter a), and the last parameter c stands for the amount of groundwater, that leaves the storage into the stream. The code in Python, with the use of Numpy arrays might look like this:

import numpy as np

# pure Python implementation of the ABC-Model

def abc_model_py(a, b, c, rain):

# initialize array for the stream discharge of each time step

outflow = np.zeros((rain.size), dtype=np.float64)

# placeholder, in which we save the storage content of the previous and

# current timestep

state_in = 0

state_out = 0

for i in range(rain.size):

# Update the storage

state_out = (1 - c) * state_in + a * rain[i]

# Calculate the stream discharge

outflow[i] = (1 - a - b) * rain[i] + c * state_out

# Overwrite the storage variable

state_in = state_out

return outflow

And how will this look like using Numba? Well, not much different (I removed the comments, since it’s basically the same).

@jit

def abc_model_numba(a, b, c, rain):

outflow = np.zeros((rain.size), dtype=np.float64)

state_in = 0

state_out = 0

for i in range(rain.size):

state_out = (1 - c) * state_in + a * rain[i]

outflow[i] = (1 - a - b) * rain[i] + c * state_out

state_in = state_out

return outflow

I run these models with random numbers as input, just to compare the computation time, and also compared the time against a Fortran implementation (see more details here). Let’s just have a look at the numbers:

# Measure the execution time of the Python implementation

py_time = %timeit -r 5 -n 10 -o abc_model_py(0.2, 0.6, 0.1, rain)

>> 6.94 s ± 258 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each)

# Measure the execution time of the Numba implementation

numba_time = %timeit -r 5 -n 10 -o abc_model_numba(0.2, 0.6, 0.1, rain)

>> 32.6 ms ± 52.7 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

# Measure the execution time of the Fortran implementation

fortran_time = %timeit -r 5 -n 10 -o abc_model_fortran(0.2, 0.6, 0.1, rain)

>> 23.4 ms ± 934 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

# Compare the pure Python vs Numba optimized time

py_time.best / numba_time.best

>> 205.15122150338178

# Compare the time of the fastes numba and fortran run

numba_time.best / fortran_time.best

>> 1.451113966128858

By adding just one decorator we are 205 times faster as the pure Python code and roughly as fast as Fortran? Well not bad, huh?

(Note that in a previous version the Numba optimized function was minimally faster than the Fortran implementation. By switching from the f2py wrapper to Cython the Fortran time was reduced, so Fortran is now a bit faster. See this pull request for further details.

I’ll end my introduction here and hope some of you are now motivated to have a look into the Numba library. My idea is to write a small series of Numba articles/tutorials in the future with more technical information, while this article should have served only as a appetizer.